A long time ago, I read voraciously.

My passion for reading dwindled when I reached college. Correlation rarely dictates causation, and in this case, it's absurd to think that seeking a degree in English "ruined" my taste for reading. It certainly never soured my taste for writing.

Nonetheless, I stopped reading. Not in a determined way or a permanent way or even a continuous way, but I read far fewer books than in the past.

Recently, while struggling with the quality of my writing and with my lack of motivation, I came to terms with something: I first fell in love with words and stories through reading, not writing. And if I mean to continue growing as a writer and storyteller—well, I have to recommit to regular reading, then, don't I?

Therefore, I reinstate my #JELreviews series!

Be warned: I am a forgiving reviewer. When you come here, you will not find me eviscerating novels. I’ll point out what I liked and what I didn’t like, and I’ll anchor everything in my opinion, rather than some self-ordained concept of what is “good” or “bad.”

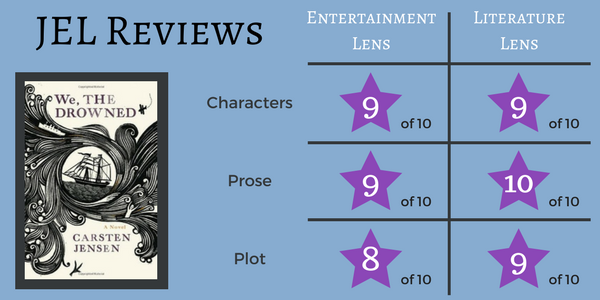

I also plan to break each review into two sections: one for those who haven’t read the book, and one for those who have read the book. I’ll rate (1) characters, (2) prose, and (3) plot through two lenses: entertainment and literature. (Basically, how I felt about it while I was reading, and how I felt about it after I'd thought about what I was reading.)

That being said, on to #JELreviews!

My passion for reading dwindled when I reached college. Correlation rarely dictates causation, and in this case, it's absurd to think that seeking a degree in English "ruined" my taste for reading. It certainly never soured my taste for writing.

Nonetheless, I stopped reading. Not in a determined way or a permanent way or even a continuous way, but I read far fewer books than in the past.

Recently, while struggling with the quality of my writing and with my lack of motivation, I came to terms with something: I first fell in love with words and stories through reading, not writing. And if I mean to continue growing as a writer and storyteller—well, I have to recommit to regular reading, then, don't I?

Therefore, I reinstate my #JELreviews series!

Be warned: I am a forgiving reviewer. When you come here, you will not find me eviscerating novels. I’ll point out what I liked and what I didn’t like, and I’ll anchor everything in my opinion, rather than some self-ordained concept of what is “good” or “bad.”

I also plan to break each review into two sections: one for those who haven’t read the book, and one for those who have read the book. I’ll rate (1) characters, (2) prose, and (3) plot through two lenses: entertainment and literature. (Basically, how I felt about it while I was reading, and how I felt about it after I'd thought about what I was reading.)

That being said, on to #JELreviews!

We, the Drowned by Carsten Jensen

For those who haven't read the book:

| We, the Drowned is long. 688 pages and 100 years long. We, the Drowned is not a normal story. This book creates its own rules. Momentary side-note: I recommend against reading it as an e-book. Paul tried, and the mid-chapter breaks collapsed, leaving him with long, unending blocks of text without any natural breaks. The paperback layout allows for plenty breaks in between mini-chapters (within the larger chapters, within the larger sections, within the large book). Those warnings delivered, however, I cannot recommend We, the Drowned with more enthusiasm. From the first page—the first lines—this book hooked me. |

Many years ago there lived a man called Laurids Madsen, who went up to Heaven and came down again, thanks to his boots.

We, the Drowned begins in 1848 during a war between Denmark and Germany. It ends with the surrender of Germany to the Allied forces at the end of World War II. The plot covers a lot of ground with skillful storytelling and delicious prose, sailing across the globe while always anchoring in one place.

The main characters come and go, but they all hail from the Danish seafaring village of Marstal. The story fixates mostly on five individuals discussed mostly in the third-person, four of them sailors—but the narrative voice extends beyond the minds of these five.

Most English writing uses either a first-person singular or third-person singular/plural narrative voice. Every so often, you'll see second-person. (See?)

We, the Drowned, from its title and forward, uses first-person plural. And the "we" isn't a specific, specified group of people. "We" can be any configuration of Marstallers: the men, the women, the children, the living, the dead, or any transient mixture thereof. Because the "we" is not a set group of actual people. The "we," the narrative voice of this novel, is the community itself.

This narrative technique is delightful and impressive. Some may find it disorienting, but I loved every moment, once I realized its implications.

The main characters come and go, but they all hail from the Danish seafaring village of Marstal. The story fixates mostly on five individuals discussed mostly in the third-person, four of them sailors—but the narrative voice extends beyond the minds of these five.

Most English writing uses either a first-person singular or third-person singular/plural narrative voice. Every so often, you'll see second-person. (See?)

We, the Drowned, from its title and forward, uses first-person plural. And the "we" isn't a specific, specified group of people. "We" can be any configuration of Marstallers: the men, the women, the children, the living, the dead, or any transient mixture thereof. Because the "we" is not a set group of actual people. The "we," the narrative voice of this novel, is the community itself.

This narrative technique is delightful and impressive. Some may find it disorienting, but I loved every moment, once I realized its implications.

We don't know if that's how it actually happened... We weren't there. We only have the notes he left us, together with the columns of figures that spelled out what proved to be the beginning of the end of our town. In telling this story, each of us has added something of his own. Our picture of him is made up of a thousand thoughts, wishes, and observations. He's entirely himself. And yet he's one of us.

I loved the tone of this book: dark and unforgiving, but with a persistent thread of hope. Terribly funny and terribly sad. As one might expect in a seafaring, war-faring novel spanning 100 years, We, the Drowned can be slow at times and strange at times. But Jensen routinely rewards the reader's commitment with catharsis and comedy and intrigue.

In my review of Terry Pratchett's Small Gods, I said, "In a few lines—in every few lines—Pratchett offers a revelation, a question, a probe into the contradictions of humanity." I've said similar of Lev Grossman's Magicians series. Most lines are works of art independent of the books themselves.

Jensen writes with the same level of skill. Every line is a gift with a new truth to contemplate. I wanted to tweet the whole dang book. And it's 688 pages long!

I recommend this book. I recommend this prose. I recommend this story. It'll stick with you—the characters live inside me now, as much as they lived in Marstal.

In my review of Terry Pratchett's Small Gods, I said, "In a few lines—in every few lines—Pratchett offers a revelation, a question, a probe into the contradictions of humanity." I've said similar of Lev Grossman's Magicians series. Most lines are works of art independent of the books themselves.

Jensen writes with the same level of skill. Every line is a gift with a new truth to contemplate. I wanted to tweet the whole dang book. And it's 688 pages long!

I recommend this book. I recommend this prose. I recommend this story. It'll stick with you—the characters live inside me now, as much as they lived in Marstal.

For those who have read the book:

Spoilers to follow!

Also, please note: in this review, I'm actively chewing on this novel, and I'll be asking more questions than offering definitive commentary.

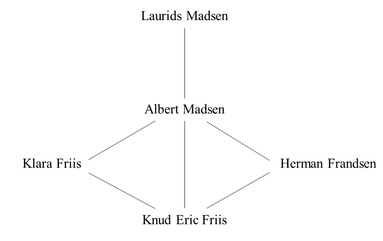

I'm a person who likes flow charts. And when I think about the point-of-view characters in this novel—the named Marstallers who take up most of the book's time—I envision the novel as below:

Also, please note: in this review, I'm actively chewing on this novel, and I'll be asking more questions than offering definitive commentary.

I'm a person who likes flow charts. And when I think about the point-of-view characters in this novel—the named Marstallers who take up most of the book's time—I envision the novel as below:

Main Characters

Each of these characters fascinates me in his/her own right. Why were these five chosen? What does this grouping say? And how does Laurids's story, which acts as something of a prologue, introduce and comment upon the stories of the four mains to follow?

Laurids Madsen

At the beginning, Laurids is our charismatic hero. We laugh with him, we struggle with him, we realize the cruel absurdity of his situation together. We love his family and we love his home.

Then, when he leaves, we mourn him as Albert mourns him—only to find the man hiding on an island with another family, named to resemble "ours." And that hurts. And by the end of Albert's journey to find his father, I hated Laurids. He'd become weak in my eyes, lazy in my eyes, heartless in my eyes.

Jensen never shields us from pain in We, the Drowned. The scene with Karo... haunts me. And he does not shy away here from rubbing salt in our/Albert's wounds.

Compared to Albert and Knud Eric, the remaining two protagonists (Klara and Herman act more as antagonists), Laurids does very little. We spend comparatively little time with him; we only get the ending of his life, really. We get all of Albert's life. And we get the beginning of Knud Eric's. (Past, present, future! With the encroaching forces of greed and vanity from Herman and Klara?)

Laurids, then, is our foundation. He is our tradition, our pain, our legends, and our painful secrets.

Laurids Madsen

At the beginning, Laurids is our charismatic hero. We laugh with him, we struggle with him, we realize the cruel absurdity of his situation together. We love his family and we love his home.

Then, when he leaves, we mourn him as Albert mourns him—only to find the man hiding on an island with another family, named to resemble "ours." And that hurts. And by the end of Albert's journey to find his father, I hated Laurids. He'd become weak in my eyes, lazy in my eyes, heartless in my eyes.

Jensen never shields us from pain in We, the Drowned. The scene with Karo... haunts me. And he does not shy away here from rubbing salt in our/Albert's wounds.

Compared to Albert and Knud Eric, the remaining two protagonists (Klara and Herman act more as antagonists), Laurids does very little. We spend comparatively little time with him; we only get the ending of his life, really. We get all of Albert's life. And we get the beginning of Knud Eric's. (Past, present, future! With the encroaching forces of greed and vanity from Herman and Klara?)

Laurids, then, is our foundation. He is our tradition, our pain, our legends, and our painful secrets.

Albert Madsen

Only Albert Madsen speaks in the first-person singular. And he only speaks in first-person singular when journeying to find his father Laurids. Because, as I'm deciding, Albert is the present. He is the crux of everything. He is the breakwater.

I liked Albert. I never stopped liking Albert. At the end, when he began his toxic relationship with Klara, I often shook my head at Albert—but I never stopped liking him, rooting for him. I believed he could make the right decision.

In the end, like Cinderella on the steps of the palace, he decides not to decide. (Into the Woods, anyone? Anyone?) (Actually, the more I think about it, some of Cinderella's conflict there legitimately mirrors Albert's conflict...) Sadly, Albert's moment trapped in the ice resolves with far more tragedy than Cinderella's moment stuck in pitch.

And his death hurt me. I mourned him. Fortunately, his protege stepped up to take his place, more of Albert's son than Albert was Laurids's.

Only Albert Madsen speaks in the first-person singular. And he only speaks in first-person singular when journeying to find his father Laurids. Because, as I'm deciding, Albert is the present. He is the crux of everything. He is the breakwater.

I liked Albert. I never stopped liking Albert. At the end, when he began his toxic relationship with Klara, I often shook my head at Albert—but I never stopped liking him, rooting for him. I believed he could make the right decision.

In the end, like Cinderella on the steps of the palace, he decides not to decide. (Into the Woods, anyone? Anyone?) (Actually, the more I think about it, some of Cinderella's conflict there legitimately mirrors Albert's conflict...) Sadly, Albert's moment trapped in the ice resolves with far more tragedy than Cinderella's moment stuck in pitch.

And his death hurt me. I mourned him. Fortunately, his protege stepped up to take his place, more of Albert's son than Albert was Laurids's.

Knud Eric Friis

Knud Eric is the culmination of everything. The entire story funnels into him and becomes his story. We watch him grow from a curious, sensitive boy to a traumatized veteran of the second World War. When he and the sailors spent their night in London swapping women as the bombs dropped around them, it felt like watching a son performing those activities.

Knud Eric, Anton, and all the crew of the Nimbus are presented to us as the storytellers. They recount Laurids's exploits, Albert's journey, and pass on the legends to younger mariners. Knud Eric carries the Madsens with him. In that way, he almost is the reader of the story with us, experiencing his own reality as if in the shadow of these weighty stories.

Knud Eric most exhibits the novel's chief theme: community. Fellowship. The positive and negative effects a society can have upon its members. Albert makes him who he is. And Albert makes him that way because of Laurids. The other children of Marstal make Knud Eric who he is. Herman makes Albert who he is. Klara makes Albert who he is. And everyone is acting based upon how the "we," the entire community, has made them who they are.

Knud Eric is the culmination of everything. The entire story funnels into him and becomes his story. We watch him grow from a curious, sensitive boy to a traumatized veteran of the second World War. When he and the sailors spent their night in London swapping women as the bombs dropped around them, it felt like watching a son performing those activities.

Knud Eric, Anton, and all the crew of the Nimbus are presented to us as the storytellers. They recount Laurids's exploits, Albert's journey, and pass on the legends to younger mariners. Knud Eric carries the Madsens with him. In that way, he almost is the reader of the story with us, experiencing his own reality as if in the shadow of these weighty stories.

Knud Eric most exhibits the novel's chief theme: community. Fellowship. The positive and negative effects a society can have upon its members. Albert makes him who he is. And Albert makes him that way because of Laurids. The other children of Marstal make Knud Eric who he is. Herman makes Albert who he is. Klara makes Albert who he is. And everyone is acting based upon how the "we," the entire community, has made them who they are.

Klara Friis

Klara is billed as an antagonist. She's an antagonist we understand, a villain we admire and respect, but a villain nonetheless. She threatens "us," our town. She disparages and ruins our way of life. And though she regrets it in the end, though she and Knud Eric welcome each other in the end, though her letters break our heart, Klara nonetheless puts everyone in an awful, unwinnable position.

The story of her and her doll Karla drives so much of her character, and Jensen utilizes this beautifully. It's a horrible, poetic moment that grows into an entire life's ambition.

Honestly, I wanted more of Klara. I wanted more action from her, but then, she represents the women who wait at home, and the inactivity of that. By having a plan, Klara steps away from that inactive, waiting role, but her plan is largely passive: do nothing; let it die.

As the main female character in We, the Drowned, Klara is strong and smart and flawed. She loves deeply, but once Albert dies, she no longer allows herself to be defined externally. But because she seeks to upset the balance between Marstal and the sea, she inevitably serves as an opposing force to the community.

Klara seeks dominance rather than fellowship, much like the other antagonist...

Klara is billed as an antagonist. She's an antagonist we understand, a villain we admire and respect, but a villain nonetheless. She threatens "us," our town. She disparages and ruins our way of life. And though she regrets it in the end, though she and Knud Eric welcome each other in the end, though her letters break our heart, Klara nonetheless puts everyone in an awful, unwinnable position.

The story of her and her doll Karla drives so much of her character, and Jensen utilizes this beautifully. It's a horrible, poetic moment that grows into an entire life's ambition.

Honestly, I wanted more of Klara. I wanted more action from her, but then, she represents the women who wait at home, and the inactivity of that. By having a plan, Klara steps away from that inactive, waiting role, but her plan is largely passive: do nothing; let it die.

As the main female character in We, the Drowned, Klara is strong and smart and flawed. She loves deeply, but once Albert dies, she no longer allows herself to be defined externally. But because she seeks to upset the balance between Marstal and the sea, she inevitably serves as an opposing force to the community.

Klara seeks dominance rather than fellowship, much like the other antagonist...

Herman Frandsen

Herman feels like an anomaly.

Laurids passed narration to his son, who passed narration to his good-as-adopted son and that boy's mother. The Madsens and the Friises are related by blood and by choice.

No one chooses Herman Frandsen as a narrative successor or partner. He's a murderer, a rapist, a pathological liar, and he's stuck in a cycle of toxic masculinity that ruins his life and continues to influence other impressionable minds on the Nimbus, and no doubt little Bluetooth after the novel's end.

We get others' points-of-view throughout the book. Anton and Markussen and plenty others take their turn in the spotlight, however briefly. Herman recurs. And I've been trying to figure out why. I've been trying to figure out why he's there at the end of it all, why he plays the role of catalyst throughout so much of the book.

In the end, he touches on many of the main themes of this novel: balance; agency; impermanence.

Herman feels like an anomaly.

Laurids passed narration to his son, who passed narration to his good-as-adopted son and that boy's mother. The Madsens and the Friises are related by blood and by choice.

No one chooses Herman Frandsen as a narrative successor or partner. He's a murderer, a rapist, a pathological liar, and he's stuck in a cycle of toxic masculinity that ruins his life and continues to influence other impressionable minds on the Nimbus, and no doubt little Bluetooth after the novel's end.

We get others' points-of-view throughout the book. Anton and Markussen and plenty others take their turn in the spotlight, however briefly. Herman recurs. And I've been trying to figure out why. I've been trying to figure out why he's there at the end of it all, why he plays the role of catalyst throughout so much of the book.

In the end, he touches on many of the main themes of this novel: balance; agency; impermanence.

Life had taught [Albert] about something far more complicated than justice. Its name was balance.

In Jensen's novel, good people do bad things. (Can we forget how Albert helped to kill defenseless Karo?) Bad people do good things. (Despite the cruel man he became, Josef Isager asked for the burial of the African's hand.) Sometimes the captain is right, and sometimes he is wrong, but we listen to him—until we don't. All remains in balance.

The narrative also places greater weight on the willingness to choose, no matter the morality or the cost of that choice. I felt like the novel suggested that agency outweighs conformity, tradition, social status. Look at its treatment of Klara: though she upsets the balance and seeks to destroy the source of the town's survival, that choice is presented as something admirable. We, like Markussen, do not understand it or agree with it—but we respect her for making a choice and exercising her agency.

And finally, this is a novel about change. A changing of the guard, a changing of the times, a changing of the world. Nothing can remain as it was, and we should accept new realities. Marstal changes over 100 years. Generations die over 100 years. Technologies advance over 100 years.

Herman embodies all of those things, even being the most despicable character in the book. And we are invited to hate him for what he's done wrong and nod in approval at his indomitability, without sacrificing one for the other. It's the complexity of this character assessment that made Herman so uncomfortable to read.

The narrative also places greater weight on the willingness to choose, no matter the morality or the cost of that choice. I felt like the novel suggested that agency outweighs conformity, tradition, social status. Look at its treatment of Klara: though she upsets the balance and seeks to destroy the source of the town's survival, that choice is presented as something admirable. We, like Markussen, do not understand it or agree with it—but we respect her for making a choice and exercising her agency.

And finally, this is a novel about change. A changing of the guard, a changing of the times, a changing of the world. Nothing can remain as it was, and we should accept new realities. Marstal changes over 100 years. Generations die over 100 years. Technologies advance over 100 years.

Herman embodies all of those things, even being the most despicable character in the book. And we are invited to hate him for what he's done wrong and nod in approval at his indomitability, without sacrificing one for the other. It's the complexity of this character assessment that made Herman so uncomfortable to read.

Overall, I have too much to say about this book. I'd have to write another book to fully analyze it! And for that reason, you should read and experience this one for yourself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed